Something to think about: How Sugar Can impact Your Mental Health

Tolle Causam

The field of nutritional psychiatry is relatively recent but is gaining momentum in terms of its evidence base and public interest.1 Several studies suggest a relationship between improved nutrition and better mental health outcomes. Epidemiological studies, together with a recent meta-analysis, show that a diet including fruits, vegetables, fish, olive oil, nuts, and legumes may lessen the chance of developing depression,2 along with a recent double-blind RCT demonstrated a significant improvement in depression severity by having an adjunctive dietary intervention.3 Many mechanisms have been studied with respect to the role of diet in mental health and illness, including micronutrients for example vitamins and minerals,4 the kind of fat,5 the outcome of food on the microbiome,6 and the influence of dietary sugar.7, 8 Sugar within the weight loss program is considered to impact mental health through several pathways including indirect ones, for example an affect on the gut microbiome.9 In this paper, we will be reporting the evidence for the direct impact of dietary sugar on the brain via its manipulation of blood sugar levels, as well as presenting information on possible mechanisms, presenting a clinical case, and sharing our clinical recommendations.

What is Glycemic Load?

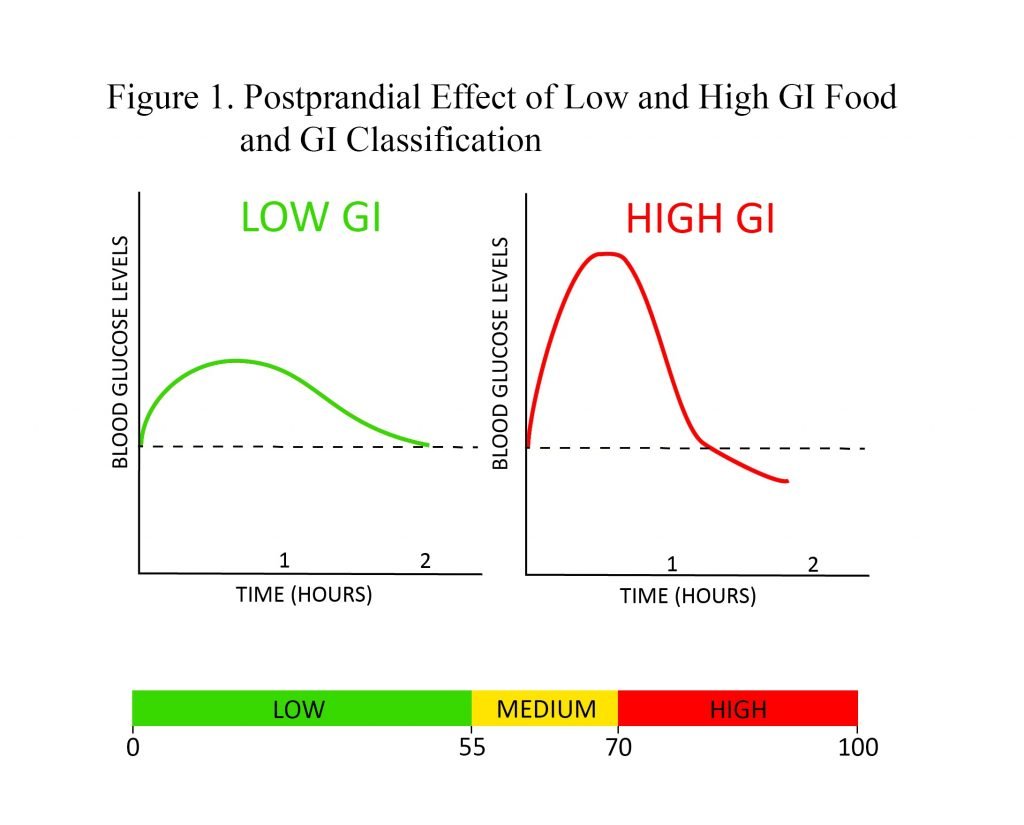

Before defining glycemic load, one must understand the idea of index list . GI is a way of measuring the postprandial effect of the carbohydrate-containing food on blood sugar levels. Low-GI foods produce a gradual rise and longer-sustained amounts of blood glucose after consumption when compared with high-GI foods, which generate a spike accompanied by a quick reduction that may dip below baseline blood sugar levels . GI may be used to assess dietary carbohydrate quality; however, it is restricted to the truth that GI values derive from consuming a serving of food which contains a specific amount of available carbohydrates . Thus, assessing diet with GI has a tendency to limit its value, as portion sizes vary drastically between individuals and would therefore elicit different glycemic responses. This is where glycemic load becomes useful.

Glycemic load is a weighted measure of GI that's calculated by multiplying a food's GI by the quantity of grams of accessible carbohydrate within the food's serving, then dividing by 100. GL is really a more useful characterization of carbohydrate consumption because it accounts for both quality and quantity of consumed carbohydrates. GL ought to be assessed using total daily dietary intake. As carbohydrate consumption can differ among diets differing in calories, GL/1000 cal has been created be the greatest predictor from the glycemic response of foods.10 You should note that both GI and GL account for available carbohydrates but not indigestible carbohydrates , as fiber passes through the gastrointestinal tract without being absorbed, thereby in a roundabout way affecting blood glucose levels. Hence, in calculating a food's GL, fiber should be subtracted from total carbohydrates. Examples of GI and GL values for some common foods are presented in Table 1.

Table 1. Examples of GI and GL of Food Servings

| Food | Serving Size | Glycemic Index | Glycemic Load |

| Corn | 1 cup | 55 | 61.5 |

| Bagel | 1 bagel | 72 | 33 |

| Cola | 12 oz can | 63 | 25.2 |

| Donut | 1 donut | 76 | 24 |

| Lentils | 1 cup | 29 | 7 |

| Peach | 1 medium peach | 28 | 2.2 |

| Broccoli | 1 cup | 0 | 0 |

| Almonds | 1/4 cup | 0 | 0 |

| Chicken | 3 oz | 0 | 0 |

Classification of the individual food as using a low, medium, or high GL is dependant on ranges presented in Figure 2. Unfortunately, GL ranges to classify overall daily intake like a low- or high-GL diet haven't been universally established, possibly due to the variability in carbohydrate requirements of various populations . In comparing GL values utilized in research, a meta-analysis of 14 studies examining the result of GL on obesity reported variable values accustomed to classify low/high daily GL, but the inclusion of these values resulted in a GL cut-off of 95 .11 While this cut-off has not been confirmed to be clinically useful, you can use it in practice as a reference.

GL makes it possible for visitors to help manage blood glucose at the gut level. Low-GL foods contain complex carbohydrates and/or a minimal quantity of available carbohydrates. Complex carbohydrates take more time to digest, producing a gradual increase in blood sugar and subsequent gradual increase in insulin. Experiencing chronic insulin spikes can lead to insulin resistance, which is related to various negative health problems, for example diabetes type 2, obesity, cardiovascular disease, and cognitive impairment.12-14 Managing blood sugar is therefore vitally important for vitality and all around health, and low-GL diets may be used to assist regulate glycemia.

GL makes it possible for visitors to help manage blood glucose at the gut level. Low-GL foods contain complex carbohydrates and/or a minimal quantity of available carbohydrates. Complex carbohydrates take more time to digest, producing a gradual increase in blood sugar and subsequent gradual increase in insulin. Experiencing chronic insulin spikes can lead to insulin resistance, which is related to various negative health problems, for example diabetes type 2, obesity, cardiovascular disease, and cognitive impairment.12-14 Managing blood sugar is therefore vitally important for vitality and all around health, and low-GL diets may be used to assist regulate glycemia.

Glycemic Load & Mental Health

Preliminary evidence shows that GL might be relevant in the pathogenesis and treatment of mental illnesses such as anxiety and depression. A multinational observational study comparing population sugar consumption and depression prevalence over a decade found a very significant correlation,15 along with a recent animal study that fed mice a high refined-carbohydrate diet for 3 months observed a rise in anxiety and depression behaviors.16 Several observational studies conducted in patients with diabetes show relationships between depression and anxiety and poorer glycemic control, although the direction of causality is unclear.17,18 A current cohort study demonstrated that increasing odds of depression and anxiety have been associated with the use of foods that have a progressively higher GI, rapport that was maintained after controlling for micronutrients recognized to play a role in mental health.19 Cross-sectional research has demonstrated a correlation between the occurrence of depression/stress and a higher consumption of sweet foods, and a large prospective cohort study showed an optimistic correlation between depression risk and a diet high in sweet desserts and refined grains.20 Conversely, it was also present in this research that top consumption of fruits and vegetables, which contain fiber that lowers GI, was of a lower risk for depression.20

In addition to the observational studies, a restricted number of interventional studies have explored a possible relationship between blood sugar levels balance and emotional and cognitive health. One medical trial assigned healthy overweight subjects to high- or low-GI diets, and located the high-GI diet led to worsening mood scores.21 Two studies assessed the outcome of high- and low-GI meals on cognitive performance in adults with diabetes type 2 and kids, respectively; both discovered that the higher-GI meal was related to poorer cognitive function.22,23 Conversely, 2 other intervention studies comparing high- and low-GI diets in patients with diabetes didn't demonstrate alterations in subclinical depression or cognitive function.20 Despite this evidence that the relationship between dietary GI and emotional and cognitive functioning may exist, no interventional studies have assessed the outcome of a low-GI or low-GL dietary intervention in psychiatric patient populations in order to assess causality of the relationship. The next case from author MA's clinical practice documents an instance of anxiety in conjunction with hypoglycemia symptoms that responded to dietary modification. This case may shed light on the function of dietary glycemic load in the pathogenesis and management of mental illness.

Case Presentation

AB is a 15-year-old female student of South-Asian descent. She given concerns of tension and the signs of hypoglycemia, in addition to difficulty concentrating, fatigue, headaches, and frequent urinary and vaginal infections.

Her anxiety met the criteria for generalized panic attacks, and she or he rated the concentration of anxiety as 8/10, . The anxiety started 3 months before the initial appointment coupled with worsened in the previous month. She described excessive worry which was difficult to control and which impacted her daily functioning. She also experienced somatic symptoms, including heart palpitations, shakiness, discomfort in her own stomach, and muscle tension. In response to the anxiety symptoms, she'd eat foods like chocolate, chips, or fruit. AB was working with a counselor to manage the anxiety symptoms and was finding some benefit.

AB had experienced episodes an indication of hypoglycemia since 12 years of age. The symptoms included muscle weakness and shaking, headaches, nausea, anxiety, and lack of concentration. Her symptoms were ameliorated by eating sweet foods.

Clinical Findings

A diet history revealed the next typical daily intake of food:

- Breakfast: fruit smoothie containing fruit, fruit juice, and water

- Morning snack: bagel with margarine

- Lunch: pasta or white rice with vegetables

- Afternoon snack: granola bar or cookies or gummy candies

- After-school meal: white pasta, which may include meat

- Dinner: white rice or spaghetti, which might include meat

- Evening snack: cookies, toast

Past Health background & Clinical Assessment

Due to her difficulty concentrating, AB had been prescribed dextroamphetamine, 5 mg. Repeat assessments of random and fasting blood glucose, as well as screening physical examination, were within normal range.

Therapeutic Approach

At the first visit, the following diet plan was prescribed:

- Breakfast: smoothie containing fruit, water, 1 scoop of protein powder, and 1 tablespoon of flax seeds or olive oil

- Lunch and dinner: incorporate a serving of protein and a serving of a vegetables

- Snacks: include protein in snacks whenever possible

- Continue previous snacks as needed for hypoglycemia symptoms

While eggs, nuts, and fish would have normally been recommended as well, the patient had an anaphylactic allergy to those foods.

Follow-up & Outcomes

At the very first follow-up, 4 weeks later, AB reported that they had complied using the diet plan. She reported a substantial decrease in anxiety , in addition to improved energy, more uncommon and fewer intense hypoglycemia symptoms, and much less headaches, in addition to improved concentration and mood. She required fewer snacks during the day and had decreased her intake of granola bars, cookies, and candies . She also reported a cessation of chronic vaginal discharge. The substantial improvement in her own anxiety symptoms prompted AB to temporarily discontinue her counseling sessions.

At a subsequent follow-up visit Four weeks later, AB reported that she had briefly reverted back to her original diet for a period of 1 week and experienced a worsening of anxiety symptoms within 1 day. After returning to the dietary intervention prescribed, her anxiety symptoms decreased within 2 days.

Mechanism of GL's Impact on Brain Health

One potential mechanism for that impact of dietary sugar on mental health is the triggering of reactive hypoglycemia. Ingestion of high-GI foods results in an increase in blood sugar levels; however, a sizable compensatory insulin release can result in reactive hypoglycemia, which is connected with an acute increase in epinephrine.24 This in turn plays a role in neuropsychiatric symptoms including anxiety and symptoms associated with anxiety, such as shakiness, sweating, and a pounding heart.25 Induction of hypoglycemia in a laboratory setting has been shown to have a negative impact on mood, hedonic tone, and levels, and to produce an rise in tense arousal.26 The existence of both anxiety and hypoglycemia symptoms within the clinical case discussed in this article, along with their concurrent response to treatment, lends support towards the hypothesis these conditions might be related.

Another potential mechanism for the outcomes of GL and mental health is increased levels of oxidative stress. Elevated blood glucose levels promote oxidative stress by enhancing the generation of reactive oxygen species, reactive nitrogen species, lipid peroxidation, protein oxidation, and decreasing antioxidant levels.27 Additionally, hyperglycemia activates the diacylglycerol protein kinase C pathway and increases manufacture of advanced glycation end-products, each of which promote oxidative stress.28 A rise in oxidative stress negatively affects mental health your clients' needs neuronal death, either directly or through generating neuroinflammation.29 Oxidative stress and inflammation have been implicated in the growth and development of depression, and higher amounts of inflammatory and oxidative stress markers happen to be noticed in depressed populations.30 In animals, increased levels of inflammation results in symptoms of depression including malaise, weakness, listlessness, poor concentration, lethargy, decreased interested, and decreased appetite.31 Administering anti-inflammatory molecules to these experimental animals blocks these effects.32 In humans, research has discovered that increasing amounts of inflammation can result in increased anxiety, irritability, hyper-arousal, and mania symptoms.32

Hyperglycemia is also strongly correlated with reduced hippocampal volumes,33 that is seen in depression34 and is associated with neuronal death. Hippocampal neurogenesis is mediated by brain-derived neurotrophic factor and associated with mood regulation.30 A decrease in hippocampal BDNF levels has been shown to be induced by a high refined-sugar diet in rats, which was also related to reduced neuronal plasticity.35

Clinical Application

Based on this preliminary evidence, as well as the well-established outcomes of GL and health conditions, modification of dietary GL in patients with mental health concerns should be considered included in a naturopathic plan for treatment. Below are some practical techniques for patients to use.

Strategies for Reducing the GL of the Meal

- Choose whole grains instead of refined grains

- Increase fiber content of the meal by including vegetables, pulses , and seeds

- Limit consumption of foods with added sugar